My husband, Adán, wasn’t sure he wanted to visit Colombia, but all through my pregnancy, I urged him to agree to the trip. Finally, I was in labour and between bouts of excruciating contractions, he squeezed my hand, “Get through this,” he said, “and we’ll go to Colombia. We’ll buy you emeralds.”

This ring comes from Bogotá’s Emerald Trade Center, a great place to purchase emeralds. Photo Adán Cano Cabrera

Eight months later I was touching down in Bogotá along with Adán and our little daughter, Alexandra. It was her first trip.

Bogotá is nestled in the Andes. Photo Adán Cano Cabrera

Adán is from Mexico, and most of his family still lives there. His mother and sister had never met Alexandra before, so they flew down to Bogotá to vacation with us. While we spent most of our time in the capital, we also enjoyed four days in Cartagena, a colonial city on the coast with UNESCO World Heritage status. In both locales, we stayed in fabulous Airbnb properties.

The first thing I needed to understand about Colombia is that I was going to have to set aside my first-world anxieties about child safety. We’d brought along Alexandra’s bulky car seat thinking we’d be able to use it. I quickly discovered, however, that seatbelts in Colombian taxis did not have the locking feature that would have enabled me to secure it. Alexandra ended up riding on my lap and, though this gave me heart palpitations, she loved it. I cradled her and sang her songs when we were stuck in traffic, and when we zipped through the streets—windows down, wind in her hair—she relished the sights.

Cartagena is well known for its colonial buildings with balconies. Photo Adán Cano Cabrera

It was going to a beach outside of Cartagena that took me to my safety-conscious limits. Our taxi driver—a father of eight!—recommended we go by motorboat to an area which, he claimed, had better food. I expressed concerns about not having a lifejacket for Alexandra, and he assured me it was a short ride and that we’d stay close to shore. Maybe it was a quick ride, but it didn’t feel like it, and we definitely didn’t stay close to shore. I clung to Alexandra and planned my strategy in case the boat sank. Meanwhile, Alexandra was unfazed by the bumpy waves and warm spray of water.

Among the various firsts that Alexandra had in Colombia, trying new types of food was the most pleasurable. A lot of the food was new to me, too, so I discovered the special thrill of experiencing fresh flavours alongside my daughter.

Colombia is a fruit-lovers paradise. As I see it, coconuts and plantains are at the heart of the country’s cuisine. Twice-fried plantains are the ubiquitous patacones, which make for a crunchy appetiser or the base for an unusual pizza, but plantains make their way onto the Colombian table in many other forms as well. I particularly loved it, along with chunks of potato and cassava, in homey bowls of chicken soup called sancocho.

The poetically named Coconut Symphony (Sinfonía de Coco) at Pastelería Mila in Cartagena. Photo Adán Cano Cabrera

Arroz con coco is white rice cooked in salted coconut milk—a typical side dish for fish. Fish itself is also cooked in coconut milk, which reminds me of certain Thai and Indian dishes minus the curry. And then there’s the dreamy Colombian version of flan that uses coconut milk as its base rather than cow’s milk.

As for other fruits, there’s mangosteen, soursop, guava, feijoa, dragon fruit, lulo, and so much more. We ate this bounty sliced, diced and whole then drank it in an endless selection of fresh juices and fruit-infused waters. Alexandra, despite my ban on juice, was drawn to the tall colourful cups and her father snuck her sips at almost every meal.

And what would Colombia be without coffee? Every day, at least once, we visited a coffee shop. In Cartagena, where we were always seeking an escape from the heat, we drank it iced. In temperate Bogotá, we preferred it hot. Once when we were in a Juan Valdez Café in a ritzy Bogotá neighbourhood, Alexandra started flashing her flirty gummy smile at a man at the next table. He took a liking to her as well, and they had an animated exchange. We soon found out that he was a Colombian telenovela star, which prompted my sister-in-law to quip that Alexandra clearly had good taste in men.

Besides lingering in cafés, we made sure to see the sights. In Cartagena, we most enjoyed our sunset stroll along the wall that rings the old part of town. It was originally built to keep out pirates, but now this wall is all about romance. There were young couples kissing and holding hands everywhere.

The author and her husband join the locals in the getting romantic on the walls of Cartagena. Photo Adán Cano Cabrera

In Bogotá and the surrounding area, highlights included wheeling Alexandra’s stroller through the Museo Botero, the Museo del Oro, and the Catedral de Sal de Zipaquirá. Museo Botero is a museum choc-o-bloc with the chubby colourful figures of Colombian artist Fernando Botero, while Museo del Oro specialises in all things gold and glittery from every corner of the pre-colonial country. Its most celebrated piece is the Muisca Golden Raft, which is connected to the many variations of the El Dorado legend.

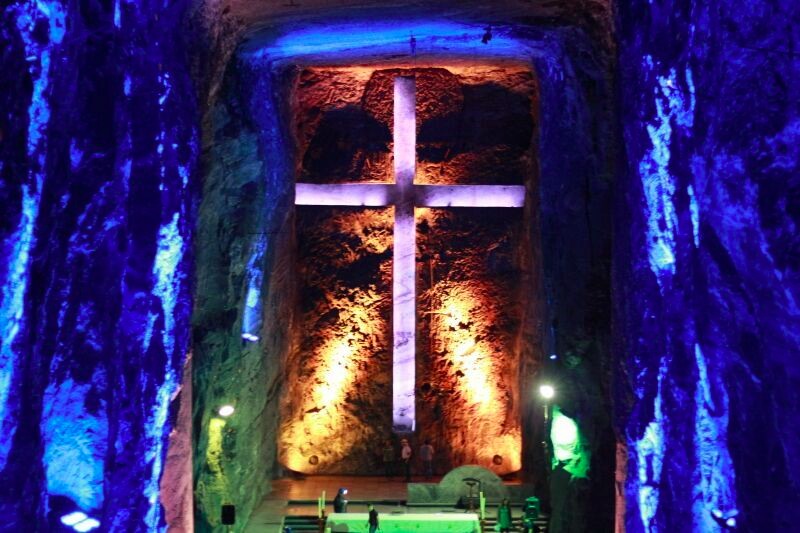

The Salt Cathedral, inaugurated in 1952, is dedicated to Our Lady of Rosary, Patron Saint of miners. Photo Adán Cano Cabrera

Catedral de Sal de Zipaquirá is a functioning church located deep underground within the tunnels of a salt mine. The church’s altar and Stations of the Cross are in ultra-modern harmony with the strange and Spartan environment, and everything is quietly aglow with coloured lights. We happened to be there for Mass, and afterwards, we headed toward the altar where the priest blessed Alexandra. Though I lean toward agnosticism and his blessing was quick, I found it touching. It reminded me of how hard we’d tried to have our little girl and how lucky we were to have her.

Before becoming Catholic pilgrimage sites, both Guadalupe Hill (pictured here) and Monserrate were sacred to the indigenous. Photo Adán Cano Cabrera

Late afternoon on our final day in Colombia, we took a funicular to the top of Monserrate, a mountain that stands guard over Bogotá. We’d hoped it would be a clear day, giving us a perfect view of the cityscape, but instead, there was a blanket of thick white fog. To make matters worse, the church at the top of the mountain was closed, so all we could do was tour the grounds. I was disappointed until—partway through the tour—I decided that the fog and the locked church didn’t matter. In fact, they were perfect. We were perched on top of a city of roughly ten million people, and it was quiet, peaceful. The Stations of the Cross were depicted with statues and flora, and the mist lent them a certain special gravitas. Through the fog, we could see another mountain, Guadalupe Hill, and its faraway statue of the Virgin glowed dramatically.

The next day, we were on a plane heading back to Canada with Alexandra in my lap and emeralds studs sparkling in my ears.

Booking.com