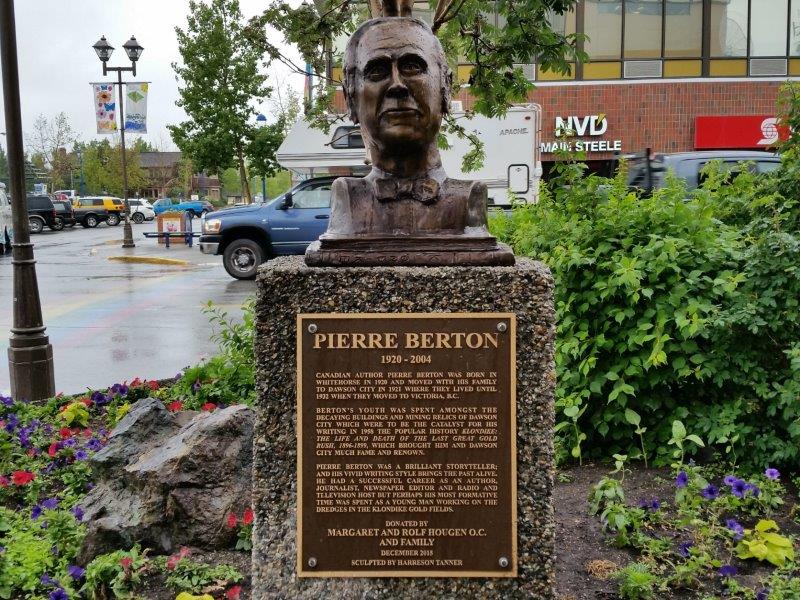

Growing up in Winnipeg, I knew about being cold, and I hated it. But I was fascinated by stories of folks who thrived in the Yukon, from Pierre Berton’s books about the Klondike gold rush to Jack London’s The Call of the Wild. I even memorized Robert Service’s poem The Cremation of Sam McGee. So, when I had the chance to visit Whitehorse and Dawson this summer, I packed my bags faster than a gold rush Stampeder. And just like them, I found the Yukon was more than I ever expected.

Bronze busts of famous celebrities like Pierre Berton line the street in Whitehorse – photo Debra Smith

The Yukon, By the Numbers

The Klondike Gold Rush began on July 10, 1897, when news finally reached San Francisco that gold had been discovered the year before at Bonanza Creek. A million desperate men swore they’d make the trip North to escape the depression that was crushing the American economy. One hundred thousand started, but only thirty thousand made it to the gold fields of Dawson and only a tenth of those got there in time to stake a claim that paid off.

(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({});

Whitehorse is named for the rapids at Miles Canyon where the Yukon River foamed like the manes of charging horses. On their way down to Dawson by boat, some people lost all their possessions, and others lost their lives in the swirling water. Today there’s a wooden suspension bridge across the river and free two-hour walking tours twice a day (Tuesday to Saturday) during the summer months led by the Yukon Conservation Society.

Still Standing

Whitehorse is full of surprises, like murals hidden on the back streets – photo by Debra Smith

Whitehorse is a thriving city and the capital of the Yukon. The 25,000 residents are fiercely proud of their city’s heritage, and their community spirit is inspiring. Bulletin boards around town are two layers deep in announcements for concerts, nature walks, annual bat counts, triathlons and the like.

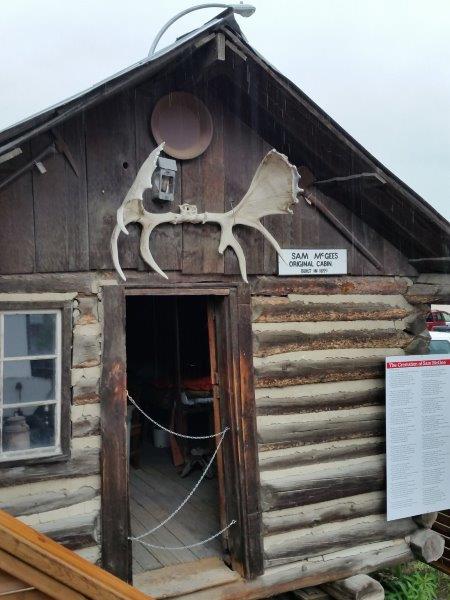

At the MacBride Museum of Yukon History, I met Executive Director Patricia Cunning. She is determined to showcase the best of Whitehorse to the world, as she did for Prince William and Kate Middleton when they visited in 2016. The state of the art building wraps around the town’s original telegraph office from 1900, which is now a telecommunications exhibit. You can take a peek into the cabin of the real Sam McGee, learn about the building of the Alaska Highway and the kids can play dress up in buffalo coats and feathered hats in the Discovery Room. There’s an impressive collection of taxidermy in the Yukon Mammals & Birds Gallery and new areas, like a recreated saloon, are being opened as they fill up with acquisitions. Cunning is currently on the lookout for the wooden inlay of a horse that graced the Whitehorse Hotel ballroom floor. In a place where materials are scarce, nearly everything including hotel room walls, windows and floors have been recycled, so there’s a good chance it will turn up. She spreads the word at the monthly free speakers’ presentations and walking tours. “Lift up your carpets”, she says, “It might be in your house.”

The new MacBride Museum of the Yukon shelters the town’s first telegraph office A giant chunk of copper sits on the corner – photo by Debra Smith

Right across from the museum is the North End Gallery. They carry a tempting variety of quality artworks and handicrafts created by local artists. After picking up a pair of earrings shaped like ravens (those huge, intelligent blackbirds are everywhere in the Yukon), I stopped at the Baked Café patio around the corner for a latte and blueberry muffin pick-me-up. Then it was time to board the restored 1925 wooden trolley car that runs beside the Yukon River on my way to visit the National Historic site of a sternwheeler, the S.S. Klondike. These huge boats were a lifeline during the gold rush before the railroads arrived. Parks Canada guides offer free tours during the day and don’t miss the documentary film with archival footage in the tent near the boat at Rotary Park.

The SS Klondike, one of the massive gold rush era riverboats used to transport goods until the 1950’s – photo Debra Smith

Rolling by the River

By the time a railroad line that ran north from Skagway and south from Whitehorse met in the town of Carcross in 1900, the gold rush had almost run its course. Like a “flash in a pan”, it was done, and prospectors were off chasing gold in Alaska. The White Pass & Yukon Route Railway still exists, and I spent a pleasant hour in Carcross before boarding chatting with some local artisans near the station.

Richard Beaudoir, owner of The Maple Rush, ages maple syrup from Quebec in whiskey barrels to produce a tasty golden syrup. “People need to know that maple syrup comes in many varieties, like fine wine”, he told me, “but you will only find this one in the Yukon”. Jewelery designer Shelley MacDonald made the news when Kate Middleton visited Carcross in 2016 and purchased a pair of her earrings, made in the shape of a traditional Inuit knife. MacDonald’s latest designs are bracelets made of silver, brass, mink and beaver fur. They’ve been featured at on the catwalk at London, England’s Fashion Week. “The people that approached me didn’t even know that Kate had been here”, she said, “I don’t know which of us was more surprised.”

(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({});

When the whistle sounded, I was aboard a 43-seater historic wooden seated WP&Y railway headed for Skagway, Alaska, upon the same route used by the Stampeders. I would disembark at Fraser, B.C. and head back to Whitehorse but there are many other options for hikers and day-trippers on the line. The sky was grey, and the tops of the spruce-covered mountains were shrouded in clouds as we barreled alongside the mercury coloured waves of Lake Bennett, past the occasional cottage and the green, tumbled remains of log cabins. There was a 45-minute stop at Bennett, just enough time to race past the museum and trudge to the top of the hill along a sandy path and get bragging rights to having set foot on the Chilkoot Trail. Rusting, iron frying pans, stoves and undefinable bars of twisted metal still lay where they were discarded over 100 years ago. At Bennet Lake, men and women who had crossed the steep, snow-covered Chilkoot Trail, again and again, to move a mandated ton of supplies on their backs, joined those who had crossed via White Pass using horses and oxen. People from every walk of life, from all over the world, most of whom had never built a boat, fashioned a flotilla to float north to Dawson. All I had to do was hit the Klondike Highway.

Bennett Lake where over 7000 Stampeders began their float down the Fraser River to Dawson – photo by Debra Smith

Daytime in Dawson

I wasn’t prepared for the heat wave in Dawson. Temperatures reached 30 degrees and air conditioning is a rarity in this town, along with basements, sidewalks and elevators, all due to the minus 50-degree Celsius winters and a ground made of permafrost. The constant freezing and thawing of the ground tosses buildings around in slow motion. So sidewalks are made of boards and buildings are raised and lowered by car jacks in the spring. Except for West Dawson, which is completely off the grid with no electricity or running water or (horrors!) internet from freeze up to break up, life in Dawson is a community affair. In July, there are 19 hours of daylight, on average and people make use of all of them.

These buildings have been left to lean to teach visitors about the hazards of permafrost in Dawson – photo Debra Smith

Walking home from the Dawson City Music Festival at 11:00 p.m., I spotted children in a playground under the twilight sky, as if was the middle of the day. Kids were happily wandering alone all over the festival grounds too, while performers like Old Man Luedacke, Skye Wallace and Elliott Brood took to the stage, but if, as it’s said, it takes a village to raise a child, Dawson (population, 1,375) is a perfect example of that village and the kids were never far from a friendly face.

Kids parents and pups enjoying an ice cream on a blazing hot day in Dawson – photo Debra Smith

Dawson has 24 buildings that make up the Historical Complex and National Historic Site, but in reality, the entire town looks like the set from a western movie. The Parks Canada walking tours are so good that I went on three of them. At the Bank of British North America, I discovered that gold is heavier than I ever imagined, and I wished I was back in time at the Red Feather Saloon, the first western Canadian bar with electric lights. I would have enjoyed a turn of the century cocktail, minus the embalmed toe. The Downtown Hotel in Dawson is famous for its “sour toe cocktail” ritual and yes, it’s a real toe.

The Klondike Institute of Art & Culture had an exhibition by the internationally known artist Emily Jan that was mysterious and beautiful and worthy of any major gallery. Diamond Tooth Gertie’s Gambling Hall, Canada’s oldest casino, took can-can dancing to a whole other, quite modern, level for the late-night show. Dining was another pleasant surprise in Dawson with a number of excellent restaurants. I’d recommend The Drunken Goat Taverna for lamb and Sourdough Joe’s Restaurant for outstanding fish dishes.

There was a real Sam McGee and his cabin is in the MacBride Museum – photo by Debra Smith

Finally, I had the chance to see where the writers who fed my fascination with the Yukon lived. I visited the modest home where Pierre Berton grew up (it’s now a writer’s retreat run by the Canada Council for the Arts); Robert Service’s cabin (everything a log cabin should be, with its sunny front porch, pot-bellied stove and well-used writing desk); and half of Jack London’s cabin (the other half is in California) – but that’s a Yukon tale that will have to wait for another time.

The writer was a guest of Travel Yukon. As always, her opinions are her own. For more photographs of the Yukon, follow her on Instagram @where.to.lady